One Strike: Jennie Williams Part I

A small, wiry woman of great intensity, Jennie Williams has lived at the Stateway Gardens public housing development for twenty-two of her forty-six years. For the last two years, she has lived in 3547 South Federal. For the previous twenty, she lived in 3617 South Federal—the first building at Stateway to be demolished. I got to know her in 1998 in the midst of the residents’ unsuccessful struggle to save their building.

Jennie is illiterate yet lives through language. Two years ago, she expressed her indignation at the prospect of being forced from her home with fierce, rapid-fire eloquence.

“I’m used to where I’m at. We’ve been living in this rat hole for—what?—twenty years. No matter what it look like, it’s home to us. A lot of people get sick and die, when they leave this building. Who wants to meet new friends, when you got old ones? People should never be less important than money. We’re not fucking animals. They may got all the money in the world, but they can’t buy my life.”

The words “they can’t buy my life” have a particular resonance coming from Jennie who grew up at one remove from slavery in the Mississippi Delta as one of thirteen children in a sharecropper family. Her mother, Savannah Williams, worked on the plantation of a man named Philpot. The Williams family was particularly prized by Philpot because it was so large.

“We used to pick cotton. Even the little ones. Philpot would say, ‘If they can walk, they can pick.’” From Jennie’s perspective as a little girl, the cotton fields stretching to the horizon seemed “never-ending.”

“Picking cotton is hard in the hot sun. Sometimes it be so hot that people fainted. From five in the morning to four in the evening, mama worked. And she had us there with her. She’d set the baby on the sack. And she was pregnant too. It was hard for her.”

Savannah Williams, according to her daughter, “wanted to be on her own—to do her own work, to plant her own things.” With the help of her first husband who was working as a crane operator in Chicago, she acquired some land and built a house.

“We had our own little home. Mama owned the land. We had cows and pigs. We growed corn, tomatoes, okra, cabbage, greens. We didn’t have to go to no store, unless we needed salt or pepper or flour. The rest of the stuff we didn’t need, cause we had it. But they ran us off.”

“Who?”

“The Ku Klux Klan, we called them, with masks on their faces and sheets. They burned our house down and our crops.”

The Red Cross and local churches provided relief and shelter for families burned out by the Klan. Jennie remembers sleeping on “a bed made of sticks” (a cot) in a barn that had been converted into a shelter. The family also stayed for a time in a house made of pegboard—until it blew away. The screen door was the only thing left standing. She laughed at the memory.

The Klan raids forced Savannah and her children back to Philpot’s plantation. “He would tell my mother, ‘You my slave.’ We were all his slaves.”

Savannah could read and write. “In those days, they had to sneak and read. The white man wouldn’t let us read. They’d whup you for that.” With a note of pride, Jennie told me that her mother wrote letters to President Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King about the conditions the family was living under in Mississippi.

Jennie first went to jail when she was three years old. She was riding on her mother’s shoulders when Savannah was arrested for participating in a civil rights demonstration in Jackson. “We were marching down the street with signs. And we were singing.” Smiling broadly, she recited the words of one of the freedom songs:

We’re gonna keep on walking and keep on talking Marching to freedom land. Ain’t gonna let nobody turn us around.

The Williams family was carried north by the last desperate wave of the Great Migration. “We escaped in the night and came on the train to Chicago.” The year was 1967. (“Martin Luther King was killed the next year.”) Jennie was eleven years old. Her first impressions of Chicago remain sharp and immediate. In the train station she encountered an escalator for the first time. “I was shocked. I didn’t know what it was. Oooo, I can’t get on that. Where’s it goin’ to take me?”

Savannah and her children stayed with other family members who had preceded them to Chicago in a crowded apartment on Lake Park Avenue. Then in 1970 they moved to the Robert Taylor Homes—to a fifteenth floor apartment in 4950 South State.

Savannah worked as a domestic. As they had worked beside their mother in the cotton fields, in the city the older children helped her clean other people’s homes.

In 1973, six years after shepherding her family to Chicago, Savannah Williams died. She was 48 years old. I asked Jennie the cause of death. “They say it was cancer,” she replied. “I say it was a lot of worry.”

Jennie was behind in school, when she arrived in Chicago. Between the demands of the cotton fields and the turbulent times in the Delta, “it was hard for us to go to school in Mississippi.” When she entered the Chicago public school system, she was placed in a grade according to her age rather than her learning level. “That’s why I never learned nothing. They didn’t even try to help me.”

By 1974, she had dropped out of school. She gave birth to a son she named Davis in 1978 and to another she named Edward in 1979. In 1980 the family moved into Stateway Gardens. In 1981 Jennie gave birth to a daughter she named Janet. At 18 months old, Janet fell to her death from a window in Jennie’s fourteenth floor apartment in 3617 South Federal. (As a result of such incidents, the CHA is now required to maintain child guards on the windows.)

“That was the hardest period of my life. I couldn’t accept she was gone. For two or three years, I was seeing things. I thought she was still here. My head was messed up. I couldn’t think.”

Jennie’s sense of home encompasses tragedy. On the eve of the closing of 3617 South Federal, she told me, “This is my building. I growed up in it, and my kids growed up in it, and my daughter died in it. If they tear it down, they’re tearing out some part of me.”

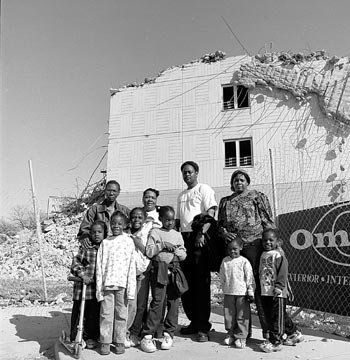

Jennie Williams (rear, left) and neighbors in front of the ruins of 3615-17 South Federal in the spring of 2001.

Today the site of 3615-17 South Federal—once the home of 230 families—is a large vacant lot at the center of the development. On the evening of August 29, 2001, Jennie walked across that open expanse to visit friends in 3651-53 South Federal. She could see, as she approached, that the police were in the building. Several police vehicles were parked outside. The grounds and lobby were deserted. “If people ain’t around, you know the police is in the building.” When she entered the lobby, she saw half a dozen plainclothes officers. One of them called out to her, “I want you to do me a favor.” He asked her to knock on doors so they could gain entrance without announcing that they were the police.

Jennie refused. They handcuffed her and patted her down. (“They touched me everywhere.”) They told her they were going to charge her with criminal trespassing—for visiting a neighboring building in the community where she has lived for more than twenty years. They would let her go, they said, if she would knock on doors for them. With great misgivings (“people get funny, if you come to their door with the police”), she agreed.

They took her to the fourth floor, removed the handcuffs, and directed her to knock on a particular door. One of the officers suggested she say she wanted to borrow some butter or sugar. No one answered her knock. They put the handcuffs back on and took her to the ninth floor. Again, they removed the handcuffs and directed her to a particular door: 909.

She knocked.

“Who is it?” a child’s voice asked.

“Jennie from next door. Is your mama home?”

A woman opened the door, and the police pushed their way in. They handcuffed Jennie and placed her on the sofa, while they searched the apartment. Jennie didn’t know the woman. She could see how upset she was.

“I seen the way she was lookin’ at me like she wanted to holler at me. I hate what I did. I was wrong.”

Jennie refused to knock on any more doors. “One of them slapped me and called me a ‘black bitch.’ ‘You shoulda did it,’ he told me. ‘Now you really goin’ to jail.'”

While she was standing handcuffed in the corridor, one of the officers urinated in front of her. “They treated me like I ain’t nothing. They made it all a joke. I didn’t think it was funny. I was upset and scared, cause I didn’t know what they were thinking of doing next.”

The police then took her to the 15th floor where “they busted out the lights and knocked in the door to an apartment.” No one was there. And they didn’t find anything.

Jennie spent three days in jail. She assumed she had been charged with criminal trespassing for visiting 3651-53 South Federal. Weeks later when the management company delivered a 10-day notice to her, she was surprised to discover that she had been charged with possession of drugs in her apartment in 3547 South Federal.