Kicking the Pigeon # 7 - “Up Under The Building”

The alleged abuses of the skullcap crew were committed in the context of what we have become accustomed to calling "the war on drugs." In view of the extent of drug use and hence distribution throughout American society, this is a strange war in that it is waged on some fronts and not others. After noting that there are five times more white drug users in the United States than black, a report issued in 2000 by Human Rights Watch states:

Blacks constitute 62.6 percent of all drug offenders admitted to state prisons in 1996, whereas whites constitute 36.7 percent. In certain states, the racial disproportion among drug admissions are far worse. In Maryland and Illinois, blacks constitute an astonishing 90 percent of all drug admissions.

— Human Rights Watch, "Punishment and Prejudice: Racial Disparities in the War on Drugs," A Human Rights Watch Report, vol. 12, no. 2, May 2000.

Blacks make up 15.1 percent of the population of Illinois and 90 percent of those incarcerated for drug offenses. What proportion of that 90 percent were arrested in Chicago? What proportion were arrested in abandoned communities such as Stateway Gardens? I raise these questions in order to suggest a perspective from which the "war on drugs" looks more like a war being waged against certain communities: the drug trade persists, while the communities are devastated.

The statistics on racial disparities in the drug war are stunning. Yet they do not fully convey the futility and absurdity of that war as it plays out from day to day in communities such as Stateway Gardens. For that, one needs a sense of what the war looks like on the ground.

* * * *

Until recently, the primary visible economic activity at Stateway, conducted openly, in the shadow of the headquarters of the Chicago Police Department, was the drug trade. An endless parade of customers passed through the drug markets in the open-air lobbies of the Stateway high-rises. Black and white, well-heeled and down-and-out, they came to buy “rock” (crack) and “blow” (heroin) from the young men in the drug trade. At various locations around the perimeters of the buildings, solitary figures stood watch for 12-hour shifts “doing security.” Most were older men and women. Almost all were drug users who supported their habits by doing this work.

Like street criers, they sang out the brand names of the drugs sold in the particular building. “Dog Face!” “Titanic!” “FUBU!” And they acted as lookouts. If they saw a police car approaching, they called out a warning—“blue-and-white northbound on Federal”—and the message was relayed from voice to voice into the interior shadows of the drug bazaar. [See “Fred Hale” for an extended interview with a former drug dealer who vividly evokes his life and work “up under the building.”]

Coming and going to their homes, residents passed through this marketplace. Day after day, they saw the same drug dealers in the same positions conducting their business in the open. Why, they asked in every available forum, can’t the police shut the drug trade down? Are the bored young men loitering in the lobbies such master criminals? Is the security system of drug addicts shouting out warnings so effective the police are unable to penetrate it? Community members don’t have the moral luxury of demonizing the young men dealing drugs. They see the sweatshop conditions in which they work. They have watched many of them grow up and drift—for lack of a job or the imagination to envision an alternative—into the drug trade. They know them in other roles besides “gangbanger”: as son or nephew, as boyfriend or teammate, as neighbor, as friend. Francine Washington, president of the resident council at Stateway, elegantly encapsulates such knowledge in the phrase “our in-laws and our outlaws.”

This orientation does not excuse criminal activity. On the contrary, desperate for some sort of relief, residents will sometimes support constitutionally suspect measures—sweeps, gang loitering ordinances, one-strike eviction policies, etc.—even at the cost of their own freedoms. They just want to see something done. From their perspective, the “war on drugs,” as waged in public housing, is at once ineffectual and abusive. The police hit the building, and the drug dealers fall back. Having knocked some heads and perhaps made some arrests, the police leave, and the dealers return. A great many arrests are made over time, but rarely do the police take into custody the major players in a given building. This ongoing exercise in futility is occasionally punctuated by police shows of force—for example, after (though not during) an outbreak of shooting between gang factions—that take the form of large numbers of officers sweeping through a building like an invading army and indiscriminately treating everyone living there as presumptively guilty of drug dealing and gangbanging.

Residents make fine distinctions among the different types of police abuse that occur under the cover of “the war on drugs.” A certain degree of excessive force is routine. For some officers, brutality is sport. They grade each other on the blows they inflict. (“That was a good one.”) Then there is the racial invective—“niggers,” “monkeys,” “hood rats,” etc.—almost invariably laced with the language of gender violence. Such words are not simply uttered under the breath; one sometimes hears them over the PA systems of police vehicles. According to residents, the practice of planting drugs is widespread; it is clearly widely feared. Above all, one hears stories of street level corruption. An African-American gang tactical officer described it to me this way: “Think of the police as the working poor. Create a situation in which there’s lots of money and drugs on the street in neighborhoods no one gives a fuck about. What do you think is going to happen?” Francine Washington jokes that the drug markets up under the buildings are “the policeman’s ATM machine—where they can go when they need to pay their mortgage or car note.” The corruption takes various forms. An arrest is made, but not all the drugs and money seized make it back to the police station. Alternatively, no arrest is made, but money and drugs are seized. (“Think of it as bail money,” a victim of this practice reported an officer saying. Another described an officer exulting after taking a large wad of cash off a drug dealer, “This year my kids are going toDisneyland!”) Then there is outright extortion—officers who demand pay-offs from drug dealers as the price of not raiding the buildings they control. At the other extreme is the practice, as one resident put it, of taking “little money” as well as “big money.” Some officers don't distinguish between drug money and grocery money. They take any cash they find in the pockets and homes of the poorest residents of the city. For years, friends at Stateway have told me that certain officers could be counted on to show up at the development on the first and fifteenth of the month—on check day.

Conditions of abandonment, in the shadow of the police headquarters, have allowed space for criminal activity by both drug dealers and police officers. The numbers of either type of criminal need not be large to have a devastating effect, for fear is a powerful magnifier. The image of the gangbanger/drug dealer looms large in the imaginations of many of us who live outside public housing, eclipsing the rest of life in communities such as Stateway. Similarly, a relatively small number of rogue police officers, if allowed to operate with impunity, can become the cruel and corrupt face of civil authority for an entire community.

Kicking the Pigeon # 6 - “Bridgeport”

Officers Seinitz, Savickas, Stegmiller, Utreras, and Schoeff were, until recently, familiar presences at Stateway Gardens and other South Side public housing developments. With the exception of Seinitz who is known as "Macintosh," they are referred to on the street not by their names but as "the skullcap crew" (they often wear watch caps) or "the skinhead crew" (several have buzz cuts). They are reputed to prey on the drug trade--routinely extorting money, drugs, and guns from drug dealers--in the guise of combating it. But what distinguishes them, above all, say residents, is their racism. Several are rumored to have swastika tattoos on their bodies. One resident described them to me as "KKK under blue-and-white." And black officers have been heard to refer to them as "that Aryan crew." "They get their jollies humiliating black folks," a former Stateway resident told me. "They get off on it."

Diane Bond, in the aftermath of her encounters with the crew, seemed stunned by the ferocity of their racism. “Me, I don’t see no color, but they’re prejudiced,” she observed. “I hear they’re from Bridgeport.”

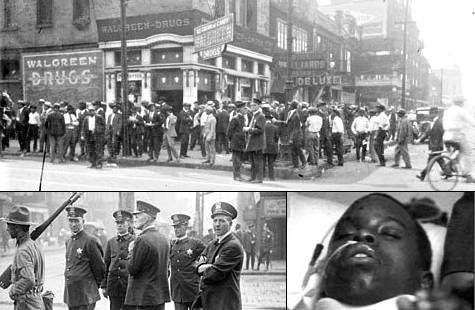

The officers were in fact assigned at the time to the Public Housing South unit of the Chicago Police Department. Until it was disbanded in the fall of 2004, Public Housing South operated out of offices at 38th and Cottage Grove in the Ida B. Wells development. The rumor that they were “from Bridgeport” was telling. For Stateway residents, “Bridgeport” carries a heavy freight of meanings and associations. It refers to the traditional seat of political power in the city. It evokes an intimate landscape containing great distances: Bridgeport is just across the Dan Ryan Expressway but a world away. And it recalls a bitter history of racial violence that includes among its defining events the 1919 riots when 4,000 blacks massed at 35th and State to defend their neighborhood against marauding white gangs, and the cruel 1997 beating that left Lenard Clark, a 13-year-old Stateway boy who had ventured into Bridgeport on his bicycle, brain damaged.

There is knowledge on the street about the skullcap crew; it resides in people's nerve endings; it flows readily between those who share a body of experience and a common language. The Bridgeport rumor reflects an effort to make sense of that knowledge by constructing a context around it. It's an effort to place the crew. Such attempts at explanation can give rise to rumors and, at least in the case of "Macintosh," to urban myths. (Last year when he was not seen at Stateway for several weeks, competing rumors circulated to explain his absence: he had been arrested in a federal sting operation; he had left the police force to become a bounty hunter; and he had gone to Iraq to fight as a mercenary.) Yet the challenge presented by the knowledge of the street remains.

As a reporter, I confront a similar challenge: to place the skullcap crew within broader contexts that help explain what at first seems inexplicable. Assume for the moment that Diane Bond's account is true. What possible rationale could there be for members of the skullcap crew to repeatedly invade her home and her body? These incidents have come to public attention because of the circumstance--highly unusual in the setting of public housing--that Bond has relationships that enabled her to get skilled lawyers to take her case. It should not be assumed because the incidents have come to light that they are the worst crimes the crew committed during the years they worked in South Side public housing communities. They may not even be the worst crimes they committed on the dates in question.

Against this background and making these assumptions, we will explore the multiple contexts that frame the Diane Bond story. Those contexts include "the war on drugs" as waged in Chicago public housing, the CHA's Plan for Transformation, and the policies and practices of the CPD with respect to complaints of police misconduct. At the center of this narrative inquiry is the question: if a group of rogue police officers operated for years in Chicago public housing with impunity, what conditions would be required to make possible their criminal careers?