Chicago Public Radio reports on Bond case and Kalven subpoena

On Tuesday, May 30, 2006, Diantha Parker of Chicago Public Radio reported on the Bond case and the City’s effort to compel Jamie Kalven to surrender his notes and other documents regarding allegations of police misconduct at Stateway Gardens.

City moves to enforce subpoena of Kalven’s notes

On June 13, 2005, Jamie Kalven received a subpoena from the City of Chicago in connection with Bond v. Utreras, et al. It demanded “copies of any and all documents, notes, reports, writings, computer files, audio tapes, video tapes, or any written or recorded item” in his possession regarding any of twenty-four named individuals (members of the Stateway Gardens community and police officers, as well as the plaintiff’s attorney and an expert witness) “and/or any allegations of misconduct by any police officer” at Stateway Gardens.

Kalven refused to comply with the subpoena on multiple grounds; chief among them, the First Amendment.

On May 1, 2006, the City filed two motions. One motion (exhibits) petitions the judge to issue “a rule to show cause as to why Kalven should not be held in contempt for his deliberate and intentional refusal to produce the notes and recordings in question.” The other motion (exhibits) seeks an order compelling Kalven to answer certain questions he declined to answer when deposed in the Bond case.

On May 30, Kalven’s attorneys, Thomas Sullivan and David Sanders of Jenner & Block, filed his response.

The case is in the courtroom of Magistrate Judge Arlander Keys. Judge Keys has said he will rule by June 12.

Heavy

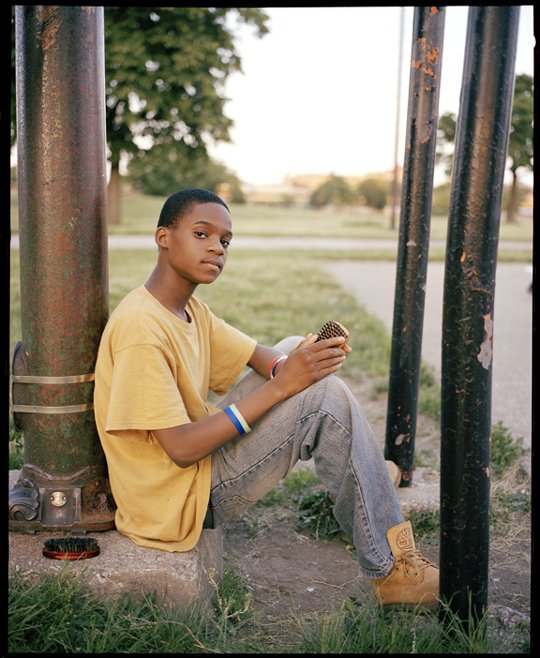

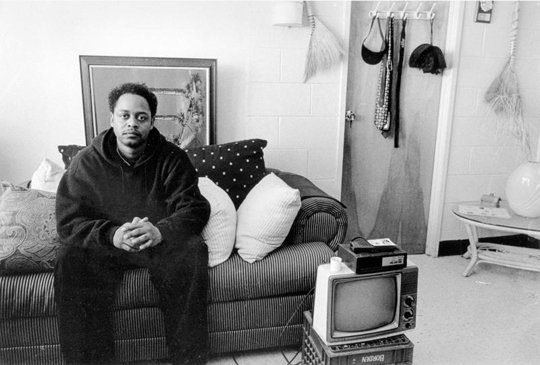

January 14, 2006. The organist played softly, as people gathered in the sanctuary of Progressive Baptist Church for the funeral of Darryl “Heavy” Johnson. Together with his friend and colleague Frank Smith, Heavy had long been the soul of the Stateway Gardens boxing gym–a sanctuary of another sort for many of those exchanging condolences and embraces in the aisles of the church. A place inhabited by Heavy’s spirit and quality of attention.

Kicking the Pigeon # 10 - Bond V. Utreras, et al

On April 12, 2004, the Edwin F. Mandel Legal Aid Clinic of the University of Chicago Law School filed a federal civil rights suit on behalf of Diane Bond. The suit names as defendants five officers—Edwin Utreras, Andrew Schoeff, Christ Savickas, Robert Stegmiller, and Joseph Seinitz—and the City of Chicago. It claims the defendants violated Bond’s constitutional rights by subjecting her to illegal searches, unlawful seizures, and the use of excessive force. It further claims they were motivated to abuse Bond by her gender and race, in violation of the equal protection provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Illinois Hate Crime Statute.

The Bond suit is the fifth federal civil rights suit that Professor Craig Futterman and his student colleagues at the Mandel Clinic have brought against the Chicago Police Department in recent years as part of an initiative called the Stateway Civil Rights Project. In my role as advisor to the Stateway Gardens resident council, I helped develop this initiative and initially brought the Bond incidents to the attention of the U of C lawyers.

On April 7, 2005, Futterman filed a motion for permission to amend the complaint to charge that Bond's abuse resulted from systemic practices and policies of the CPD, and to add as defendants Philip Cline, the superintendent of police, Terry Hillard, the former superintendent, and Lori Lightfoot, the former administrator of the Office of Professional Standards. On June 6, the court granted the motion.

The theory of the amended complaint is that the City had a de facto policy of “failing to properly supervise, monitor, discipline, counsel, and otherwise control its police officers,” and further that top police officials were aware “these practices would result in preventable police abuse.” As a result, Futterman argues, members of the skullcap crew knew they could act with impunity. The City and the high officials named in the suit were thus complicit in their abuses.

The case is in the courtroom of Judge Joan Humphrey Lefkow. In the aftermath of the murders of her husband and mother on February 28, Judge Lefkow's cases have been handled by Judge Charles Kocoras, chief judge of the Northern District of Illinois. In mid-July, Judge Lefkow returned to the bench on a limited basis. She is expected to return full-time in the fall.

The City’s defense strategy in Diane Bond v. Chicago Police Officers Edwin Utreras (Star No. 19901), et al is straightforward: each officer denies having had any contact with Diane Bond on any of the dates she claims she was abused. In their reply brief to a motion seeking access to police photos for the purpose of identification, the City attorneys make reference to “the highly unusual and outlandish allegations of abuse in this case” and to “the vague and reckless nature of plaintiff accusations”—language that suggests they will seek to portray Bond as unstable and delusional, that they will argue the abuses she alleges are figments of her imagination.

The City lawyers employ two basic tactics to impeach Bond’s credibility. They stress at several points that she was not arrested, as if this somehow undermines her claims of abuse:

Plaintiff states that although severely victimized and humiliated by the police officers, she was never arrested or taken to a police station as a consequence of her alleged interaction with the police officers. [emphasis added]

The fact she was not arrested is relevant to the issue being addressed in the brief—access to police photos—for the absence of the documentation provided by arrest reports makes identification of the officers involved a central issue. The brief’s phrasing and repetition, however, go beyond that point to imply Bond cannot have been “severely victimized and humiliated by the police officers,” because she was not arrested in any of the incidents. This line of argument contributes to the aura of impunity that is one of the most disturbing aspects of the case. It reminds one uncomfortably of the logic of “disappearances” in Latin America and elsewhere: because there is no arrest, the state has deniability.

The second means by which the City attorneys seek to impeach Bond’s account is to emphasize repeatedly that her physical injuries are inconsistent with her allegations of abuse. For example, with respect to the first incident, they state:

Despite the elaborate description of physical abuse she gave, as of April 15, 2003, plaintiff had only a dime size area of swelling under her right eye for which she sought no medical treatment (See Exhibit C, D, report of OPS investigator Grace Wilson).

The City seeks, in effect, to narrow “abuse” to “physical abuse.” In her OPS interview regarding the April 13th incident, Bond states she was slapped once in the face and kicked once in the side. One sentence of the two-and-a-half page interview is devoted to this physical abuse. The “elaborate description” of abuses that constitutes the bulk of the interview details a series of assaults that caused serious injury without leaving marks on her body. She describes, among other things, having an officer put a gun to her head; witnessing officers destroying her property, including religious objects sacred to her; looking on while officers struck her teenaged son; being forced to disrobe and expose herself under the gaze of a male officer; watching the police beat a man they had brought into her home; and seeing her son and his friend forced to assault that man—to put on a demeaning show for the amusement of the officers—as a condition of release. The injuries inflicted by these abuses were not the kind that could be documented by a trip to the emergency room.

The City’s defense strategy of flat denial necessarily hinges on attacking Bond’s credibility. How far is the City prepared to go down this road? A chilling possibility is that it will seek to use Bond’s history of sexual violence against her. One form this might take would be to argue that the effect of the multiple violations she suffered in her youth has been to make her delusional. Another approach would be to exploit patterns of denial and victim-blaming predictably provoked by cases of sexual violence (especially when multiple incidents are alleged) and argue that she has a history of making unsubstantiated accusations of sexual abuse. Will the City use the acquittal of the five boys charged with raping her thirty years ago for this purpose? Will it offer, in defense of the skullcap crew, that Bond’s own mother didn’t believe her when she blurted out as a small child that her step-father was abusing her?

Kicking the Pigeon # 9 - March 29 and 30, 2004

A question persists at the center of this narrative. Why? Assuming Diane Bond's account is true, why did members of the skullcap crew repeatedly invade her home and her body? What possible rationale could there be for their conduct? The abuses occurred in the context of the "war on drugs." That was the pretext for raiding her building, searching her home and person, and interrogating her. But does the enforcement of drug laws, in the absence of individualized suspicion (much less a search warrant supported by probable cause), explain the abuses? Does it make sense of the senseless, sadistic conduct alleged? This is not an easy question to answer. For it demands we entertain the possibility that the abuses were an end in themselves and the drug war a vehicle to that end: the possibility that members of the Chicago Police Department terrorized Diane Bond for the perverse pleasure of it.

I recall arriving at 3651 South Federal on a winter day in 2003, just as an unmarked police car was driving away. Once it was out of sight, the drug marketplace up under the building would reopen for business. Several people were standing outside the building, looking on. Among them was a woman known on the street as Betty Boop, who acts as a lookout for drug dealers to support her heroin addiction.

“You know what that crazy man did?” she asked me, referring to one of the officers. “He just walked up and kicked that bird for no reason.”

She pointed to a pigeon on the pavement. It was wobbly and disoriented—in obvious distress.

“Now why did he have to do that?” Betty asked.

The image comes back to me now, as I try to make sense of the patterns of the skullcap crew: kicking the pigeon. Casual cruelty can become a way of life in a setting where everything is permitted, where you enjoy de facto dominion over other human beings who are by definition not to be believed. Any account they might give as victims or witnesses is impeached in advance, for they are gangbangers and drug dealers. They are the mothers and grandmothers of gangbangers and drug dealers. They are residents of a public housing development that is seen less as a community than as a loose criminal conspiracy to engage in gangbanging and drug dealing. Some officers are made uncomfortable by the license this perverse logic confers upon them; they know if they don’t restrain themselves, nobody else will. And some exult in the power it gives them to toy with other human beings.

Seen in this light, it was not something threatening about Diane Bond that drew the skullcap crew to her. It was something vulnerable.

* * * *

In early March of 2004, ten months after her last encounter with the skullcap crew, I visited Bond in what is now the lone surviving building at Stateway Gardens. It stands at the center of thirty-three acres of vacant land. Waiting for her to answer the door, I was struck anew by how exposed her situation was: a woman alone on the eighth floor of a half-vacant high-rise in the middle of a desert of demolition. There was a hand-lettered sign affixed to the door:

Stop!!! Read Don’t Knock On my Door Unlest It For a Good Cause (Not Stupid)

The reason for the sign, she explained, was that the police had told her they would arrest her, if she let anyone they were after into her apartment.

I found Bond despondent. She was unemployed. She was broke. She had fallen behind on her rent. Her isolation had deepened because she could no longer afford a telephone. And her fear of the police seemed only to have intensified with the passage of time.

“I can’t stand," she said, "that I’m scared even to open my door.”

She spoke of the gang rape she suffered in high school with startled immediacy as if it had occurred recently rather than thirty years ago.

“All these years,” she said, “I’ve been holding it inside.”

As I listened to her talk about her sense of exposure and helplessness, I was reminded of an image a friend once used to describe how people “recover” from traumatic violence. It is, she said, akin to the way the body responds to tuberculosis. One does not get over TB by excising it or expelling it from the body; rather, the body walls off the bacteria and contains them. Similarly, the victim of terrorizing violence rebuilds her world, containing but not erasing the virulence that has entered her life. In this sense, a traumatic event changes the underlying terms of existence. It remains present within one’s nervous system and soul as a continuing vulnerability. Even when one has rebuilt one's life, the trauma may under certain circumstances be reawakened with the force and immediacy of the original assault. And so for Diane Bond, it appeared, her encounters with the skullcap crew had reopened the wounds of earlier violations. While the crew presumably wasn’t aware of her history of sexual violence, it’s not hard to imagine they had picked up the scent.

Finding Bond in despair, I could see more clearly how gallantly she had responded over time to the cruelties she had suffered as a young woman. As the structure of a building is revealed by the process of demolition, so the design of the life she had built for herself after violence was poignantly evident. She had invested herself in her work and her family. She had found solace in religion; prayer and counting her blessings were part of her daily routine. And she had been deeply embedded in her community, moving through it gracefully without evident fear, enjoying the passing encounters and conviviality of the street. It was these structures of meaning and security, this hard-won sense of being at home in the world, that were now collapsing.

* * * *

At about 11:30 p.m. on March 29, 2004, Bond was descending the stairs from her apartment. In the stairwell she encountered Officer Robert Stegmiller and another officer. Stegmiller had a screwdriver in his hand. He ordered Bond to come with him and threatened to stick her in the neck with the screwdriver if she didn’t comply. The two officers seized her, threw her to the ground, twisting her arm behind her back, then handcuffed her.

“I screamed and screamed. No one came,” she said. “‘You know me,’ I hollered. ‘I live here. I’m Diane Bond.’”

The officers pulled her up off the ground and removed the handcuffs.

Stegmiller put a finger to his lips. He warned her not to say anything about what had happened.

After the officers released her, Diane went to Michael Reese Hospital where she was examined and outfitted with a sling.

The next evening, she encountered Stegmiller outside her building. She was wearing the sling on her right arm. He called out to her in a mocking tone, “What happened to you?”

Bond fled the building and went to the Stateway Park District field house. Clyde Johnson of the Park District saw that she was in distress. He talked with her and tried to reassure her. A man of considerable personal command, seasoned by sixteen years at Stateway, Johnson was struck by how terrified she was. In a sense, he saw her injury, her trauma.

“It kind of scared me," he recalled. "She was actually shaking. Trembling. She was petrified.”

Johnson noticed she had soiled her pants. He let her take refuge in his office, amid the sports equipment, until the field house closed at 10:00 pm.

The basis for this narrative is a series of interviews with Diane Bond, beginning on March 30, 2004 and continuing to the present; an interview with Clyde Johnson; and the plaintiff's statement of facts in Bond v. Chicago Police Officers Utreras, et al.

Officer Robert Stegmiller denies having any contact with Ms. Bond on the dates alleged.

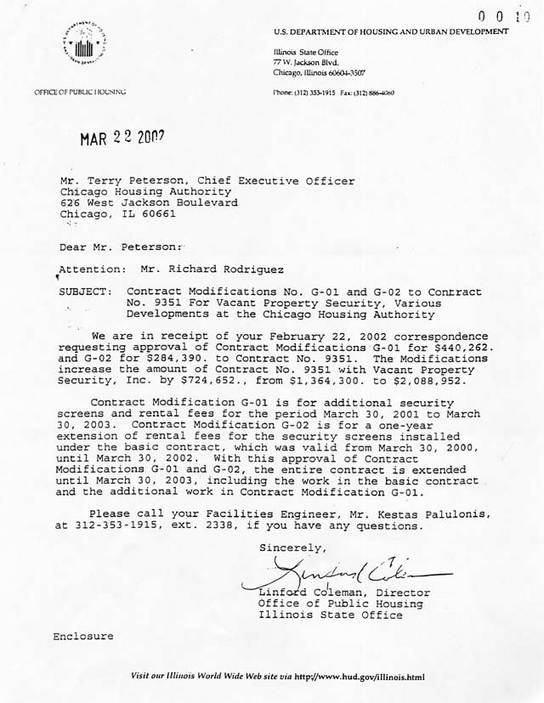

Kicking the Pigeon # 8 - The CHA Plan And Public Safety

The launching of the Chicago Housing Authority's Plan for Transformation in 1999 promised an end to the abandonment and exploitation of CHA communities. Terry Peterson, the CEO of the CHA, is eloquent on the theme that public housing residents are citizens of Chicago with equal claims to its services. Among the first things the City did after launching the Plan was to disband the 270-member CHA police force. The policing of public housing was shifted to the Chicago Police Department, which created a public housing unit and, drawing on a $30 million federal grant for the purpose, hired additional officers to staff it.

The attractive principle that CHA residents are full citizens of the City turned out in practice to be less a new standard of care and accountability than a rationale for shifting federal resources intended for public housing residents to other city agencies, such as the Department of Human Services, the Park District, and the Department of Aging, as well as the CPD. By the end of 2004, the CHA had transferred more than $60 million from its budget to the CPD. (If one adds CHA funds given to the CPD specifically for the Cabrini-Green and Henry Horner developments, the total comes to more than $70 million.) One can imagine arguing that this transfer of funds was required to facilitate a transition to a new regime of respectful, sustained law enforcement. That is not, however, the argument the CHA made. Rather, it stated in a resolution presented to its Board of Commissioners that the funds were being transferred to the CPD for the purpose of securing “supplemental police services, which are defined as over and above the baseline police services provided to residents of the City of Chicago.”

The CHA reiterated its stance on public safety for its tenants in a 2003 exchange with Thomas Sullivan, the former U. S. Attorney who served as the independent monitor of the relocation process during 2002-2004. In one of his reports, Sullivan had expressed concerns about unchecked gang activity in buildings undergoing relocation and in buildings to which families were being relocated. The housing authority stated in its reply:

CHA has provided a higher level of security for CHA residents than any citizen of Chicago receives through the Chicago Police Department.

It’s hard to know how to characterize this statement. Sullivan called it “incredible.”

Over a period of five years, I witnessed the entire relocation process at Stateway. I frequently visited each building as it went through relocation; and I lived through the process on a daily basis in the building where my office was located. There is no reason to assume conditions at Stateway—relative to other developments undergoing relocation—were uniquely bad. On the contrary, one might expect them to be somewhat better, if only for public relations reasons, in view of the proximity of the police headquarters two blocks away

Yet at no point during these years was effective, respectful policing provided on a sustained basis. The reality at Stateway—and, I assume, at other communities being “transformed”—is that, as the onsite community contracted to six buildings, then to four, then to two, and ultimately to one, the quality of policing did not significantly improve. In their final months, the Stateway buildings descended into purgatorial conditions exploited by both the drug trade and by police officers parasitic on it.

That is not to say that the policing of Stateway has not been better at some times than others. For some months last year and early this year, in response to complaints from the resident council, there was an around-the-clock police presence at 3651-53 S. Federal, the one surviving high-rise. It took the form of a squad car parked in proximity to the building. The officers rarely got out of the car, but at least they performed a scarecrow function sufficient to deter open drug dealing. In recent months, the police presence has been intermittent, and drug dealers have been drifting back into the building.

Whatever the fluctuations in police presence over time in response to crises and public pressure, there has been no evidence of a plan or strategy to provide minimally adequate law enforcement to public housing communities on a sustained basis. Just as the City did not maintain the buildings in the expectation they would soon be demolished, so it did not invest in nurturing the relationships necessary to effective law enforcement. After all, what does "community policing" mean in the case of a community in the process of being dismantled?

In retrospect, it is clear that CHA’s public safety plan for these communities has been their erasure. Such is the logic of abandonment: conditions that should be the basis for calling public institutions to account are invoked by those very institutions in support of their agendas. Thus, the CHA’s failure to maintain the high-rises becomes the rationale for their demolition. And the CPD’s failure to provide adequate law enforcement in public housing communities becomes the rationale for obliterating those communities and starting over. This logic helped create the space through which, according to residents, the skullcap crew moved, living off the land and abusing community members at will, in the last years of high-rise public housing.

Kicking the Pigeon # 7 - “Up Under The Building”

The alleged abuses of the skullcap crew were committed in the context of what we have become accustomed to calling "the war on drugs." In view of the extent of drug use and hence distribution throughout American society, this is a strange war in that it is waged on some fronts and not others. After noting that there are five times more white drug users in the United States than black, a report issued in 2000 by Human Rights Watch states:

Blacks constitute 62.6 percent of all drug offenders admitted to state prisons in 1996, whereas whites constitute 36.7 percent. In certain states, the racial disproportion among drug admissions are far worse. In Maryland and Illinois, blacks constitute an astonishing 90 percent of all drug admissions.

— Human Rights Watch, "Punishment and Prejudice: Racial Disparities in the War on Drugs," A Human Rights Watch Report, vol. 12, no. 2, May 2000.

Blacks make up 15.1 percent of the population of Illinois and 90 percent of those incarcerated for drug offenses. What proportion of that 90 percent were arrested in Chicago? What proportion were arrested in abandoned communities such as Stateway Gardens? I raise these questions in order to suggest a perspective from which the "war on drugs" looks more like a war being waged against certain communities: the drug trade persists, while the communities are devastated.

The statistics on racial disparities in the drug war are stunning. Yet they do not fully convey the futility and absurdity of that war as it plays out from day to day in communities such as Stateway Gardens. For that, one needs a sense of what the war looks like on the ground.

* * * *

Until recently, the primary visible economic activity at Stateway, conducted openly, in the shadow of the headquarters of the Chicago Police Department, was the drug trade. An endless parade of customers passed through the drug markets in the open-air lobbies of the Stateway high-rises. Black and white, well-heeled and down-and-out, they came to buy “rock” (crack) and “blow” (heroin) from the young men in the drug trade. At various locations around the perimeters of the buildings, solitary figures stood watch for 12-hour shifts “doing security.” Most were older men and women. Almost all were drug users who supported their habits by doing this work.

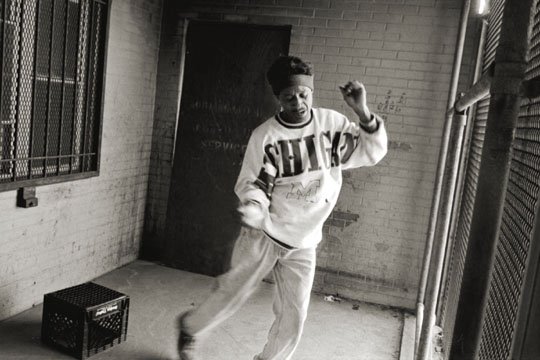

Like street criers, they sang out the brand names of the drugs sold in the particular building. “Dog Face!” “Titanic!” “FUBU!” And they acted as lookouts. If they saw a police car approaching, they called out a warning—“blue-and-white northbound on Federal”—and the message was relayed from voice to voice into the interior shadows of the drug bazaar. [See “Fred Hale” for an extended interview with a former drug dealer who vividly evokes his life and work “up under the building.”]

Coming and going to their homes, residents passed through this marketplace. Day after day, they saw the same drug dealers in the same positions conducting their business in the open. Why, they asked in every available forum, can’t the police shut the drug trade down? Are the bored young men loitering in the lobbies such master criminals? Is the security system of drug addicts shouting out warnings so effective the police are unable to penetrate it? Community members don’t have the moral luxury of demonizing the young men dealing drugs. They see the sweatshop conditions in which they work. They have watched many of them grow up and drift—for lack of a job or the imagination to envision an alternative—into the drug trade. They know them in other roles besides “gangbanger”: as son or nephew, as boyfriend or teammate, as neighbor, as friend. Francine Washington, president of the resident council at Stateway, elegantly encapsulates such knowledge in the phrase “our in-laws and our outlaws.”

This orientation does not excuse criminal activity. On the contrary, desperate for some sort of relief, residents will sometimes support constitutionally suspect measures—sweeps, gang loitering ordinances, one-strike eviction policies, etc.—even at the cost of their own freedoms. They just want to see something done. From their perspective, the “war on drugs,” as waged in public housing, is at once ineffectual and abusive. The police hit the building, and the drug dealers fall back. Having knocked some heads and perhaps made some arrests, the police leave, and the dealers return. A great many arrests are made over time, but rarely do the police take into custody the major players in a given building. This ongoing exercise in futility is occasionally punctuated by police shows of force—for example, after (though not during) an outbreak of shooting between gang factions—that take the form of large numbers of officers sweeping through a building like an invading army and indiscriminately treating everyone living there as presumptively guilty of drug dealing and gangbanging.

Residents make fine distinctions among the different types of police abuse that occur under the cover of “the war on drugs.” A certain degree of excessive force is routine. For some officers, brutality is sport. They grade each other on the blows they inflict. (“That was a good one.”) Then there is the racial invective—“niggers,” “monkeys,” “hood rats,” etc.—almost invariably laced with the language of gender violence. Such words are not simply uttered under the breath; one sometimes hears them over the PA systems of police vehicles. According to residents, the practice of planting drugs is widespread; it is clearly widely feared. Above all, one hears stories of street level corruption. An African-American gang tactical officer described it to me this way: “Think of the police as the working poor. Create a situation in which there’s lots of money and drugs on the street in neighborhoods no one gives a fuck about. What do you think is going to happen?” Francine Washington jokes that the drug markets up under the buildings are “the policeman’s ATM machine—where they can go when they need to pay their mortgage or car note.” The corruption takes various forms. An arrest is made, but not all the drugs and money seized make it back to the police station. Alternatively, no arrest is made, but money and drugs are seized. (“Think of it as bail money,” a victim of this practice reported an officer saying. Another described an officer exulting after taking a large wad of cash off a drug dealer, “This year my kids are going toDisneyland!”) Then there is outright extortion—officers who demand pay-offs from drug dealers as the price of not raiding the buildings they control. At the other extreme is the practice, as one resident put it, of taking “little money” as well as “big money.” Some officers don't distinguish between drug money and grocery money. They take any cash they find in the pockets and homes of the poorest residents of the city. For years, friends at Stateway have told me that certain officers could be counted on to show up at the development on the first and fifteenth of the month—on check day.

Conditions of abandonment, in the shadow of the police headquarters, have allowed space for criminal activity by both drug dealers and police officers. The numbers of either type of criminal need not be large to have a devastating effect, for fear is a powerful magnifier. The image of the gangbanger/drug dealer looms large in the imaginations of many of us who live outside public housing, eclipsing the rest of life in communities such as Stateway. Similarly, a relatively small number of rogue police officers, if allowed to operate with impunity, can become the cruel and corrupt face of civil authority for an entire community.