Denial of Access to Access Denied: Part II

In view of the urgent need to secure vacant units at CHA developments across the city, and in view of the CHA’s responsibility to make prudent use of limited resources in order to improve the quality of life for residents, how is it that a vendor offering a competitive, if not superior, product for securing vacant units at a significantly lower price has been consistently put at a disadvantage by the CHA while another vendor has been favored? Why has this situation been allowed to persist? How will it be corrected?

The View raised these questions at the end of an inquiry, posted April 22, 2002, into allegations that the CHA had over several years allowed Vacant Property Security, Inc. (VPS) a de facto monopoly, while systematically excluding Access Denied, a company offering a comparable product. (See “Denial of Access to Access Denied.”) Recent events have helped answer some of these questions, and they have sharpen others.

Significant development is the release by the CHA of documents requested by Access Denied under the Freedom of Information Act. Although the documents are incomplete, they support allegations of misconduct in the contracting process. By allowing us a glimpse into the molecular structure of this process, they raise questions, extending beyond this set of contracts, about the CHA’s capacity to make cost effective use of its resources and to reform longstanding patterns by which funds allocated for housing those in need are siphoned off by contractors.

In order to grasp the issues, it is necessary to bring close attention to a series of documents and to hold in mind the pattern they form. Bear with me, for this is a paper trail that has immediate implications for the safety and well-being of public housing residents.

The story begins in December of 1998 when Peter Bately, the owner of Access Denied, came to Chicago in response to an invitation from the CHA. David Anderson, manager of technical services, arranged for a demonstration by Access Denied of its product. Mr. Anderson sent the following e-mail to six senior colleagues:

I am planning to schedule a presentation of a security door and window product called Access Denied, which appears to be conceptually similar to the product marketed by Vacant Property Security. I would like to schedule the demonstration for Tuesday, December 15 at 4700 at 1:00 pm. Please plan to attend if at all possible.

At this point, VPS and Access Denied were on an equal footing: two vendors with “conceptually similar” products that address an essential operations need of the CHA: the securing of vacant units. (On the critical nature of the need, see “In Memory of Eric Morse” – Part I and Part II.)

* * *

In May of 1999, VPS and Access Denied had their first opportunity to bid on a CHA contract. On the advice of Mr. Anderson, Access Denied set its price at $135,600.00. VPS won the contract with a bid of $105,875.00. According to Mr. Bately, had Access Denied based the bid on its own price structure, its bid would have come in at $93,600.00.

The contract was awarded to VPS, although they did not meet the specifications. On the bid document, signed by Frank Cureau, the president of VPS, there is a handwritten note:

We could start immediate installation using our standard range of equipment and change to the purpose [sic] made product (free of charge) as they become available.

In other words, VPS acknowledged that they did not meet the specifications and indicated that they would do so when they began manufacturing (as opposed to using existing inventory) for the purpose of fulfilling the contract.

The matter of the specifications is not a technicality. It is fundamental. VPS did not satisfy the specification that panels must be “secured . . . with braces and threaded bolts.” Instead, it used cable. Property managers who have used both VPS and Access Denied report that it is this feature that makes VPS panels relatively easy to breach.

Was it legitimate for the CHA to award the contract to VPS under these circumstances? Arguably, VPS, despite coming in at a lower price, should not have received the contract, because they didn’t meet the specifications. In a sense, there was no real basis of comparison on price between the two bids, in view of the fact that one met the specifications and the other didn’t.

Did VPS subsequently conform to the specifications? Did those managing the contract at the CHA demand that they do so? If VPS did not conform to the specifications and hence was in violation of the terms of the contract, was it legal for the CHA to award the company subsequent contracts?

* * *

On September 20, 1999, the CHA issued “Specifications for Bid” #29855—a sizeable contract to secure vacant units at CHA developments throughout the city. The bid document lists two “acceptable manufacturers“: Vacant Property Security Inc. and Access Denied.

Access Denied was concerned about bond requirements stipulated by the contract. They ultimately decided not to bid, because they were unable to resolve this point with the CHA.

VPS, too, was concerned about the bond requirements. David White of VPS wrote Deborah O’Donnell of the purchasing department:

We have today had a series of meetings with our insurance company regarding the issuing of a performance bond and having duly considered all aspects have decided that we would regretfully have to withdraw from bidding on this contract if it remains a condition. . .

These conditions have never been demanded from us any previous contract in over 20 years of trading on both sides of the Atlantic and we therefore consider them inappropriate and unacceptable for this type of rental contract.

Trusting you will be able to suitably amend the current document, we assure you of our continued attention.

In the end, VPS did bid on the contract, while Access Denied did not. On October 14, 1999, the bids were opened. There were two. VPS was the lowest bidder and was awarded contract #9351 in the amount of $1,364,300.00. The contract period was March 30, 2000 through March 30, 2002.

The documents secured thus far under the Freedom of Information Act do not include the CHA’s response to the letter from VPS quoted above. Was the bid document amended? Were the bond requirements waived for VPS? Were they ignored?

* * *

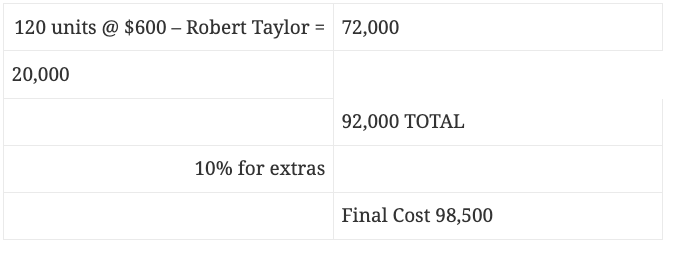

Among the documents released under the Freedom of Information Act is a purchase order, dated January 21, 2000, issued to VPS in the amount of $98,500.00. A note on the purchase order reads: “Sole Source approved by Mr. Jackson.” This is presumably a reference to Phillip Jackson, who was at the time the chief executive officer of the CHA.

Sole source is a procedure under which a contract is granted without going out to bid, because there is only one source for the service or product being sought. In light of the provision in the bid document quoted above to the effect that there are two “acceptable manufacturers”—VPS and Access Denied—how could a sole source contract be justified in this instance?

The purchase order describes the work for which the CHA contracted:

There are a couple of things to note here. First, the addition of 10% of $92,000.00 does not yield a total of $98,500.00. Second, it appears that the rationale for sole source was that the contract called for relocation of existing VPS doors at Madden Park. That makes sense: VPS could plausibly be said to be the sole source for the purpose of removing and reinstalling its own product. But what is the justification for treating the bulk of the contract for new doors at the Robert Taylor Homes—$72,000.00 of the $98,500.00 contract—as sole source? If this is permissible, then restrictions on the use of sole source can easily be evaded by treating contracts which contain some sole source services as sole source in their entirety.

* * *

On June 1, 2000, Bridget Reidy, Chief Operating Officer of the CHA, sent a letter to Linford Coleman, Director of the Operations Division of the Department of Public Housing in the Illinois office of HUD, seeking approval of a sole source contract with VPS. I will quote this remarkable document in its entirety:

Dear Mr. Coleman:

The Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) seeks the approval of your office to enter into a sole source agreement with Vacant Property Security, Inc. (VPS) to provide CHA with products and installation services defined as “Short Term System” (STS).

CHA entered into contract #9351 with VPS for the use of products and services defined as “Long Term System” (LTS), which were specifically designed for use at properties that CHA is in the process of vacating. What we have found, however, is that by using combinations of the LTS and STS systems CHA can reduce its costs associated with securing entire floors or buildings. For example, CHA priced the cost of securing 230 entrance doors at 3615-17 S. Federal under both LTS and combination of LTS and STS products. Using the LTS system exclusively, the cost would have been $95,450. However, by using a combination of LTS and STS products, CHA’s cost is only $23,540, because by using the products in combination, it was only necessary to secure each entry door in the building.

Given CHA’s need to vacate and secure large high rise buildings, this appears to be the best use of available funding. Since VPS provides a proprietary product designed to be used only with other products that it manufactures, it is necessary to award this contract on a sole source basis. To our knowledge, no other manufacturer offers a product that can be used in combination with VPS’s LTS product line.

Should you have questions or require additional information, please contact David Anderson, Manager of Technical Services at 312.567.7720, extension 179.

Sincerely,

M. Bridget Reidy, Chief Operating Officer

On July 17, 2000, Terry Peterson, chief executive officer of the CHA, received a response to Ms. Reidy’s letter from Mr. Coleman. It reads in relevant part:

We have reviewed the subject documents requesting HUD approval and determined that a sole source agreement with Vacant Property Security, Inc. would be cost-effective. Approval is granted to award the contract to Vacant Property Security, Inc.

Now let’s return to Ms. Reidy’s letter and examine it more closely. She explains that VPS has two products—the “LTS and STS products.” By combining “the LTS and STS systems,” she writes, “CHA can reduce its costs associated with securing entire floors or buildings.”

The strong impression left by the letter is that the LTS and STS systems are two different product lines and that the most cost-effective approach requires the meshing of the two systems. In fact, they are two different pricing systems for the same product—long-term (i.e., rental on a yearly basis) and short-term (i.e., rental on a monthly basis).

Ms. Reidy provides an example of the savings achieved by using the LTS and STS systems in combination: the securing of 3615-17 S. Federal, the first building closed at Stateway Gardens:

Using the LTS system exclusively, the cost would have been $95,450. However, by using a combination of LTS and STS products, CHA’s cost is only $23,540, because by using the products in combination, it was only necessary to secure each entry door in the building.

As advisor to the Stateway Gardens resident council, I was deeply involved in the process of securing and ultimately closing 3615-17 S. Federal. I was in the building daily over a period of months. The savings described by Ms. Reidy were achieved by securing entrances to entire floors rather than securing individual units on those floors. This is a sensible, cost-effective approach. It has nothing to do with “using a combination of LTS and STS products.” And it has nothing to do with any unique quality of VPS products. It is simply a strategic decision as to how best to deploy the housing authority’s resources for securing buildings—whether it is using VPS, Access Denied, or some other vendor.

Ms. Reidy asserts that it is only through coordinated use of VPS’s LTS and STS products that the CHA can achieve these substantial savings. Here is the crux of her argument:

Since VPS provides a proprietary product designed to be used only with other products that it manufactures, it is necessary to award this contract on a sole source basis.

She adds:

To our knowledge, no other manufacturer offers a product that can be used in combination with VPS’s LTS product line.

This is asserted, despite the documented fact that the CHA was aware of Access Denied and had in the bid document issued on September 20, 1999 named VPS and Access Denied as “acceptable manufacturers.”

I do not know who wrote this letter. It is possible, perhaps likely, that it was not written by Ms. Reidy but rather was prepared for her signature by another member of the CHA staff. I do know—on the basis of its wording and design—that the person who wrote it intended to misrepresent the realities and to mislead the reader. It is a fiction that can have had only one purpose: to secure more CHA business for VPS on an exclusive basis, while excluding its competition.

There is a final mystery left unanswered by this document: what contract is Ms. Reidy seeking to have approved as a sole source contract? So far as can be discerned from the documents, there is no pending or forthcoming contract being put out to bid at the time. VPS is working under contract #9351 in the amount of $1,364,300.00. Does Ms. Reidy’s letter to HUD reflect an effort to convert #9351 into a sole source contract, so that it can thereafter be extended and supplemented indefinitely without going out to bid? Is the CHA, in effect, asking HUD to approve a blank check made out to VPS?