One Strike: Jennie Williams Part II

On May 29, some nine months after her arrest on August 29, 2001, Jennie Williams was evicted from her apartment at Stateway Gardens. She was evicted, although the criminal case arising from the events of August 29 is still in progress. The eviction cost her not only her home in a community where she has lived for more than twenty years, it also cost her the benefits of lease compliance under the CHA’s Plan for Transformation—a Section 8 voucher and the opportunity to return to the mixed income development to be built at Stateway. In the course of the eviction case, her claim that she was the victim of police misconduct was never heard and considered by the judge.

Assuming the veracity of Jennie’s account, it would be comforting to believe this outcome was produced by a malfunction of an otherwise workable system. Experience at Stateway and elsewhere, however, suggests the more disturbing possibility that what happened to Jennie is a common rather than exceptional outcome. In One-Strike cases the criminal law and civil law operate on their own terms and in their own spheres. No one is accountable for the results; no one is responsible for adding up the sanctions. But for the One-Strike defendant, criminal and civil law are braided together into a single system—a system that might have been designed, in collaboration, by Rube Goldberg and Franz Kafka.

That is the system Jennie Williams has been trying to understand and navigate since August 29, when she stepped out to visit a friend and encountered the police.

Since last fall, she has been juggling court appearances—the drug case in criminal court and the eviction case in housing court. “It’s confusing,” she said. “So many court dates.”

As many public housing residents do, Jennie made the common sense assumption that if she prevailed in her drug case, the eviction case would necessarily be resolved. She hired a lawyer to represent her in the criminal case. While she didn’t neglect the eviction case, she gave it less priority.

“I wasn’t worried about it [the eviction case], cause I know the police was wrong. I know it’s up to me and the police and the judge. I had my faith.”

That faith may have been misplaced. At every stage, she has been frustrated in her efforts to be heard.

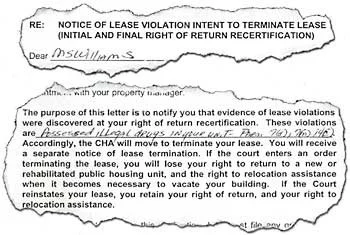

When she received a 10-day notice—the document that initiates the eviction process—she went to the management office to try to explain what had happened. They told her that there was nothing they could do; it was out of their hands. They had no discretion in the matter.

She then attempted to secure representation in the eviction case from the Legal Assistance Foundation of Metropolitan Chicago [LAF]. She met with a lawyer and left the meeting thinking that the lawyer would appear on her behalf at her first court date on January 3. Neither the lawyer nor Jennie appeared in court. Jennie returned to the lawyer who, she says, instructed her on how to file the neccesary motion. It was granted by the judge presiding in her case, Judge Jane L. Stuart. Thereafter Jennie tried repeatedly to contact the lawyer but never received a call back.(On the day she received a letter informing her that the judge had entered an eviction order in her case and that the sheriff could come at any time, she also received a letter from the LAF lawyer stating that she had been unable to reach Jennie at the phone number she had provided.)

So Jennie was left to manage the eviction case on her own. Judge Stuart set the next court date for March 12. On that date, Jennie was present, but the police failed to appear. Judge Stuart continued the case to April 2. Because she is illiterate, Jennie is dependent on others to read documents to her. In this instance, she confused the date. She thought her next court date was on April 12 rather than April 2.

On April 2, the police appeared in court. Jennie did not. The police testified that on August 21, they arrested her for possession of drugs in her apartment. No counter-evidence was offered. The judge entered a judgment for the CHA and ordered Jennie evicted.

Several days later, the police who arrested Jennie on August 29 appeared at her door. Jennie wasn’t there. They told her daughter-in-law to tell her she had been evicted.

On April 12, Jennie arrived at the courtroom at the appointed time and found another judge presiding. Realizing her mistake, she sought the advice of a member of the Stateway management staff who advised her to file a motion to reopen the case. With assistance of the help desk on the sixth floor at the Daley Center, Jennie filed a motion pro se (i.e., on her own behalf) to vacate the order to evict. The affidavit she submitted outlined allegations of police misconduct.

The lawyers for the property management company strongly opposed her motion. “They said I was playing games.” Judge Stuart denied the motion.

At the suggestion of Kate Walz of the National Center on Poverty Law, I put Jennie in contact with Christine Farrell of the Cabrini Green Legal Aid Clinic who agreed to make an emergency appeal on her behalf.

We had an extended meeting with Ms. Farrell during which Jennie demonstrated great command of detail with respect to the two legal proceedings she is involved in. When I remarked on this, she replied, “I have to remember it all, because I can’t write it down.”

Ms. Farrell noted that often when police misconduct is alleged, there are no witnesses and the defendant’s testimony is assumed to be self-serving. In Jennie’s case, however, others saw that she was under arrest and was being forced to knock on doors in 3651-53 South Federal—among them, the woman whose apartment the police searched. Also, residents living on Jennie’s floor in 3547 South Federal are prepared to testify that the police made no arrest on August 29 at her apartment.

Jennie thus had a strong case, said Ms. Farrell. The challenge would be to get the court to hear that case.

After listening to Ms. Farrell sketch the arguments she planned to make, Jennie said of her own efforts to be heard, “That’s what I tried to tell judge, but she wouldn’t let me.”

Ms. Farrell was particularly bothered by the fact that she routinely appears before Judge Stuart to make the same motion Jennie made and has it granted, while Jennie presenting the motion pro se was denied.

I asked Doran Harper, the manager at Stateway Gardens, to instruct the attorneys for the management company not to rise objections to the emergency motion to vacate. He told me that managers had no discretion in One Strike matters and referred me to Brenda Parker, the CHA asset manager for Stateway. Ms. Parker in turn arranged a conference call with Stephanie Horton, the CHA lawyer who oversees One Strike cases. Ms. Horton agreed to direct the attorneys to stay eviction pending the outcome of the appeal, on the condition that I cover any costs associated with staying the eviction, which I agreed to do.

On May 16, Judge Stuart heard Ms. Farrell’s emergency motion to vacate. The attorneys for the management company again objected to reopening the case. Judge Stuart denied the motion.

Emerging from the courtroom, Ms. Farrell was as upset as Jennie.

“Every time I tried to say that there were merits of the case that need to be heard, the judge stopped me,” she reported.

The motion having been denied, Jennie’s eviction went to the top of the pile. The net effect of our efforts to intervene may well have been to accelerate her eviction.

Several days later, I asked Jennie how she was doing.

“I’m scared, and I’m tired. My hair is coming out. It ain’t fair, when I know I didn’t do anything wrong.”

On the morning of May 29, the sheriff evicted Jennie. I saw her later in the day. She had been weeping.

“I’ve been crying all day,” she said. “I’m hurtin’. I hate this. What they’re doin’ is wrong.”

Jennie has put her belongings in storage and is staying with one of her sisters in Englewood. She comes back to Stateway almost every day.

Ms. Farrell has initiated an appeal in the Illinois Appellate Court.

In a recent conversation, Jennie recalled her mother’s courage—how she had fought for her rights in the Mississippi Delta during the civil rights movement.

“She was marching down there. She’d get locked up for her rights. She’d rebuild and they’d burn her house back down again and tear up her land.”

“So she kept fighting for her home in the South, and now you’re fighting to keep your home here,” I suggested.

“It’s about the same, isn’t it?” she said tentatively. “You kinda wonder if there’s a connection.”