Restoring The View

Today The View From The Ground resumes publication. It has been two years since we last posted a story. The reasons for this hiatus are personal. We certainly had not completed our mission. Nor had we exhausted the possibilities of The View. We were just beginning to grasp the nature of the tools that we, in collaboration with our readers, were developing.

We resume publication today in a radically altered landscape. Several years ago, I joked in print that the name of Chicago’s public housing strategy—“The Plan For Transformation”—was Orwellian: the Chicago Housing Authority, which had failed to provide “maintenance” and “security,” was now promising “transformation.” (Only as the process gathered momentum, did I realize that the truly Orwellian word was “plan.”) Yet the name has, in fact, proved accurate.

When we posted our first story in the spring of 2001, the Stateway Gardens public housing community, the ground from which we viewed the city, was largely intact. Today the “State Street corridor,” dominated by the Robert Taylor Homes and Stateway Gardens, has indeed been transformed. No other word will do. Once the largest concentration of public housing in the nation, it is now a post-apocalyptic landscape, block after block of vacant land. Of the twenty-eight high-rises that comprised Robert Taylor, two remain standing; of the eight Stateway buildings, one remains. At these and other former public housing sites throughout the city, developers have erected billboards proclaiming the names of the new “mixed income communities” they are building on the land cleared by demolition. Stateway Gardens, for example, has been renamed “Park Boulevard.”

Until recently, a billboard promoting Park Boulevard stood at the corner of 35th and State, the northern boundary of Stateway. The sign was a montage of photographic images: a boy blowing on a dried dandelion, a grandfather with his arm draped around his grandson, a little girl held aloft by strong, loving arms. Lightly superimposed upon these images were a series of words: “family, dreams, life, diversity, laughter, happiness, hope, fun, together, learning, independence, sharing, success.” Four words were in a darker font than the rest. They occupied the foreground and formed the phrase:

A Community Coming Soon

This message was meant to be read with reference to the acres of vacant land to the south of the billboard. It was intended to promote the idea that the developers would create on this blank slate a new community embracing the qualities evoked by the words on the sign. The inescapable, if perhaps unintended, subtext of this message was that those words did not apply to the generations of Stateway residents for whom this place had been home. The redevelopment process is necessarily blind to the forms of community they have created. It is a process of erasure rather than renewal.

For two years, The View reported from the Stateway community, as it contended with the forces pushing it toward invisibility. The words “the view from the ground” suggest both a moral stance and a methodology. Our understanding of what they mean has deepened over time. In our initial statement of purpose, we wrote:

The tradition of reporting from which The View takes its bearings seeks to create the means for those who are voiceless and caricatured within the prevailing discourse to be heard and seen on their own terms.

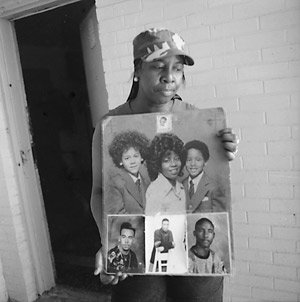

This is not to claim, as some have said, that The View “gives voice to the voiceless.” Those in abandoned communities such as Stateway, who are barred from full participation in the society by conditions of structural exclusion, do not lack voices. They lack the means of self-representation. Using the crafts and media at our command, we have tried to make immediate the voices of those who have told us their stories.

We have done so as friends, as neighbors, and, in some instances, as actors in those stories. For a number of years, we have been deeply engaged in the life of the Stateway community. How does our solidarity with those we report on affect our reliability as reporters? Does it distort our vision? Or does it perhaps afford us access to perception? These are legitimate questions. We leave them to our readers to assess. We make no claims to journalistic “objectivity.” We do aspire to intellectual rigor. As the British journalist James Cameron observed in his memoir Point of Departure:

I still do not see how a reporter attempting to define a situation involving some sort of ethical conflict can do it with sufficient demonstrable neutrality to fulfill some arbitrary category of “objectivity” . . . . I may not always have been satisfactorily balanced; I always tended to argue that objectivity was of less importance than the truth, and that the reporter whose technique was informed by no opinion lacked a very serious dimension.

We have understood our work within the traditions of human rights reporting. This form of inquiry begins with the injury to human dignity in the individual case. Having established the reality and unacceptability of the abuse, it moves to interrogate larger systems. Is this instance part of a larger pattern? What is the extent of that pattern? What conditions contribute to the space in which such abuses occur?

This orientation is, for us, an essential aspect of the meaning of “the view from the ground.” We have sought to engage fundamental human rights issues by immersing ourselves in eight square blocks of the South Side–by staying close to the ground.

Today most of that ground, cleared and fenced, awaits redevelopment. Life persists amid the ruins. Some seventy-odd families inhabit the one remaining building, 3651-53 South Federal. Community members who have relocated elsewhere return to see friends, to hang out, to walk familiar streets. The Park District field house–known as “the center”–remains full of activity. Yet it would be false and sentimental to understate the extent of the damage.

The machinery for disappearing people and erasing places is stunningly effective. We published The View from an office in a first floor apartment in one of the Stateway high-rises, 3542-44 South State. I knew everyone in the building; everyone knew me. I wrote a good deal about that building and know many more stories than I have written. After the building was closed, I came back almost every day over a period of months, sometimes for hours at a time, to bear witness to the process of demolition. Yet if I stand today on the vacant lot where 3542-44 South State was located, it takes a large, sustained effort of imagination to remember what was there.

Whatever else might be said about Chicago’s vertical ghetto, you could see it. As you moved through the city, it was difficult not to see public housing high-rises. Even registered in passing at the periphery of your vision as you drove by at 60 mph on the expressway, they posed questions, unsettled the mind, and abraded the conscience. The invisible ghetto fast replacing the high-rises allows us to move through the city unimpeded by moral friction and relieved of the danger of colliding with fundamental issues of social justice.

This restructuring of the city, it is important to recognize, is also remapping the geography of our moral imaginations—what we can see and what we can think, how issues are constructed and the parameters within which they are discussed.

It has been said that the more effective a regime of censorship is, the less people are aware of it. Some struggles over freedom of speech

have taken the form of demanding that censorship be kept visible, e.g., that material suppressed from publications be shown by white space (in India during the State of Emergency) or by ellipses (in Poland under martial law). (The latter practice gave rise to an inspired Solidarity button that read simply: “. . . “) Something similar can be said of structures of exclusion: the more invisible they are, the more effective. The less we are aware of them, the more powerfully they shape our experience of the world. They are part of the given; we are inside the whale. This is, arguably, the ultimate paradox of the Plan For Transformation: as the City has torn down the high-rises, it has fortified the structures of exclusion.

Paul Farmer has observed:

Human rights violations are not accidents; they are not random in distribution or effects. Rights violations are, rather, symptoms of deeper pathologies of power and are linked intimately to the social conditions that so often determine who will suffer abuse and who will be shielded from harm. If assaults on dignity are anything but random in distribution or course, whose interests are served by the suggestion that they are haphazard?

Narrative inquiries into the conditions underlying patterns of abuse must move against a powerful undertow. The boundaries of permissible discourse, the conventions of “on the one hand. . . on the other hand” journalism, and, in some instances, the very structure of the built environment resist such narratives. The costs of perception are high. It is easier to see assaults on human dignity as malfunctions of otherwise sound policies and institutions (the work perhaps of “a few bad apples”) than as “symptoms of deeper pathologies of power.”

We have no illusions about how difficult it is to tell such stories. It is not simply a matter of providing reliable information. Good journalistic work can readily be assimilated to the prevailing structures of perception. It is necessary to subvert those structures—to break through—in order to create space for fresh perception. This is the work of art and nonviolent resistance, as well as human rights reporting. The View is a point of intersection between these traditions, sensibilities, and conversations.

The View will continue to report from the ground. We will report from the places to which people have been disappeared. And we will describe the machinery by which individuals, populations, and issues are rendered invisible. Above all, we will work to develop narrative, analytic, and graphic strategies to illuminate the pathologies of power.

We don’t know where our inquiries will take us. We have a strong sense of direction but no map. We invite readers to join our ongoing conversation about how best to tell particular stories. What are the requirements of the narrative? the most effective lines of inquiry? the best means of making the invisible visible?

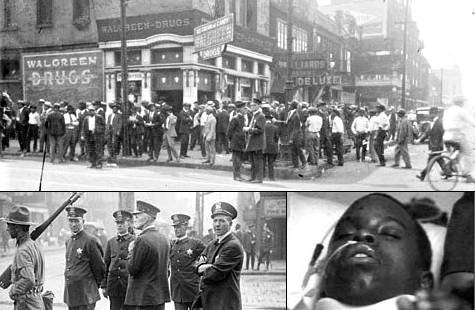

This much is clear. Conditions of structural exclusion are ultimately enforced by violence: by particular blows inflicted by particular hands on particular bodies. That is our point of departure—the ground from which we take our bearings—as we now resume The View.

About

The View From the Ground is an occasional publication of the Invisible Institute—a set of relationships and ongoing conversations grounded at the Stateway Gardens public housing development on Chicago’s South Side. In the tradition of human rights monitoring, our aim is to deepen public discourse by providing reliable information about conditions on the ground. The View orients from the perspective of those living in abandoned communities. There are, we recognize, other perspectives on the changes transforming inner city neighborhoods. We are mindful of these perspectives. Our first responsibility, however, is to evoke the experience of those on the ground—those for whom these neighborhoods are home. Public discourse is deformed by the absence of this perspective. The View seeks to inject it into the public conversation. Investigative journalism and human rights reporting are often challenged on the ground that they do not afford the powerful an adequate opportunity to tell their side of the story. Such criticism is based on a misconception about the nature of such reporting. Powerful institutions and individuals do not lack vehicles for expressing their views and asserting their interests. The tradition of reporting from which The View takes its bearings seeks to create the means for those who are voiceless and caricatured within the prevailing discourse to be heard and seen on their own terms. Such reporting does not purport to be “balanced” in the sense that the reporting in the mainstream press does. (Indeed, one of its aims is to correct distortions that arise from the conventions of “objective” journalism.) That does not, however, mean that it claims an exemption from high standards of craftsmanship and rigor. On the contrary, the moral authority of a human rights monitoring effort rests ultimately on the quality of its reporting. That is the basis on which we expect The View to be judged.

Help Us

The View From The Ground is dedicated to enriching the public conversation about a range of issues associated with abandoned communities. We need your help to broaden and deepen that conversation. If you find The View useful, if you think it provides information and access to perception not available elsewhere, we ask that you help us extend its reach. Who do you know who might benefit from The View? Please recommend it to them and urge them to subscribe. Do you know of networks through which The View might be made available? If so, please let us know. The View is a tool for holding public institutions accountable to the marginalized and disenfranchised. Its impact has exceeded our expectations.That impact would be further enhanced, if public officials and other decision-makers knew it was being read and discussed by an expanding number of engaged citizens. Thanks for your help in spreading the word.