Vol. 3 Issue 2

A Note from Jamie Kalven & Update on Green v Chicago

Ana, 17, looks up an officer’s disciplinary history on the Citizens Police Data Project at a protest in Chicago, 2020, Photo: Pat Nabong/AP

A Note from Jamie Kalven

I want to acknowledge a debt. The police killing of George Floyd in the context created by the pandemic has brought together the perspectives of public health and public safety in such a way that only the willfully blind can fail to see the structural violence that deforms American society. The confluence of these perspectives has carried me back to the moment when I first became aware of Dr. Paul Farmer.

It was 2003. At the time, I had been working in and reporting from the Stateway Gardens public housing development—eight square blocks of Chicago’s South Side—for the better part of a decade. I had several roles. I directed a “grassroots public works” program dedicated to creating economic alternatives for young men in the criminal economy and emerging from prison. I served as advisor to the resident leadership, participating in negotiations with the housing authority, HUD, and private developers. And, together with Patricia Evans and David Eads, I produced the first incarnation of The View From The Ground—a human rights reporting project we conceived of as a form of urban samizdat.

The work at Stateway was personally compelling yet difficult to explain. Following moral intuitions where they took me, I lacked the words to adequately describe the path I was on. In an odd reversal for a writer, I found it easier to act than to explain.

At that moment in my life and work, several friends independently urged on me a recently published book by Tracy Kidder titled Mountains Beyond Mountains: The Quest of Dr. Paul Farmer, a Man Who Would Cure the World. They suggested I would find the subject of the book a kindred spirit. What I found was an exemplar of human rights advocacy whose work illuminated my inchoate intuitions and whose words made a gift of my own experience, providing me with the means to make sense of what I was in the process of learning from my years of immersion in an abandoned community.

Listen to his voice:

Human rights violations are not accidents; they are not random in distribution or effects. Rights violations are, rather, symptoms of deeper pathologies of power and are linked intimately to the social conditions that so often determine who will suffer abuse and who will be shielded from harm. If assaults on dignity are anything but random in distribution or course, whose interests are served by the suggestion that they are haphazard?

There is a lot to unpack in this passage. Note the way Farmer deploys his authority as a doctor to diagnose the “pathologies of power.” Unlike some advocates of an epidemiological approach to violence, he doesn’t use the public health perspective to sanitize the discourse of the questions of power and powerlessness. Rather, he goes straight at them with bracing moral clarity, while calling out ways we go about not knowing what we have the means to know about “assaults on dignity.”

The persuasive power of Farmer’s voice—and his singular impact on global public health policy—are grounded in the way he has subjected himself to his subject. For decades, he immersed himself in rural Haiti, bringing a quality of attention to his patients that defied the prevailing assumption in international development that it is “inefficient” to provide the same level of care to the poor as to the well-to-do in affluent countries.

Central to his practice is a principle as simple as it is radical: listen to those most directly affected by the pathologies of power. Victims of structural violence—a favorite Farmer term—know things that much of the rest of society is organized and mobilized not to know. Only by accessing that knowledge is it possible to achieve diagnostic clarity. “Human rights abuses,” he has written, “are best understood (that is, more accurately and comprehensively grasped) from the point of view of the poor.”

Returning to Farmer’s work in recent weeks in an effort to gain perspective on our engulfing new reality, I have been reminded of how deeply his perspective has shaped the orientation of the Invisible Institute. No one has better stated the question that drives our work on police abuse and impunity:

By what mechanisms, precisely, do social forces ranging from poverty to racism become embodied as individual experience?

Jamie Kalven

August 7, 2020

Earlier this year, in Green v. Chicago Police Department,

a judge ordered the City of Chicago to produce all completed police misconduct investigations back to 1967—roughly 175,000 files. Thus far, the Invisible Institute has received some 23,500 investigative files, which it is in the process of absorbing into the Citizens Police Data Project.

Convicted in 1985 as a 16-year-old of a quadruple murder on the basis of a confession he claims was coerced by detectives, Charles Green has pursued every avenue open to him in his effort to establish his innocence. Toward that end, in 2015 he filed the Freedom of Information Act request at issue in this case.

The City has appealed the judge’s ruling. It has also entered into an agreement with Mr. Green, to settle his case. Under the terms of the settlement, he will waive his claims to the documents in exchange for $500k. Mr. Green, who is indigent and in poor health, is not in a position to reject the City’s offer.

The proposed settlement must be approved by the City Council. It was scheduled to be presented at the Council’s July 22 meeting. An op-ed in the Chicago Tribune by Jamie Kalven alerted council members and the public to the consequences for transparency of approving the settlement in its present form. Confronted with expressions of concern by a number of aldermen and growing public pressure, the Council deferred voting on the settlement until its September 9 meeting.

The upshot is that while the settlement remains pending, space has opened up to craft a policy for releasing the investigative files. Major stakeholders—members of the City Council, the Lightfoot administration, and Mr. Green’s lawyer—have all expressed openness to such a process. It remains to be seen what that process will yield. Stay tuned.

For more, read Maya Dukmasova’s report in the Chicago Reader and Josh McGhee’s interview with Mr. Green in the Chicago Reporter. A network of churches—the Redemptive Justice Coalition—has organized a GoFundMe campaign in support of Mr. Green.

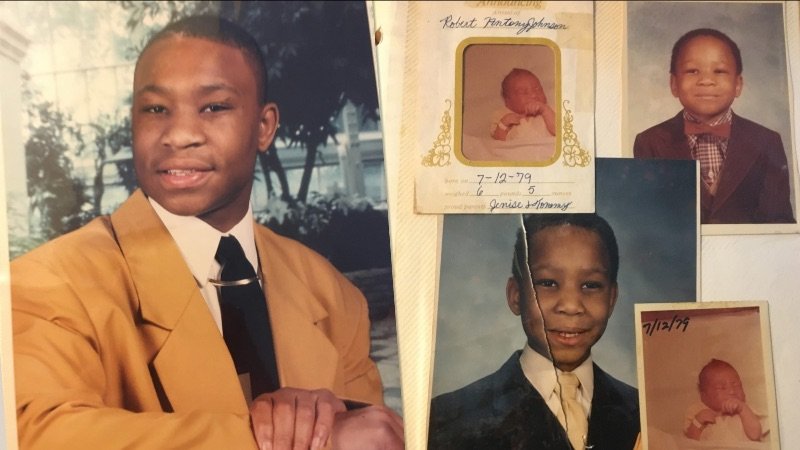

In May, the Invisible Institute published a yearlong investigation into the wrongful conviction of Robert Johnson that unearthed substantial new evidence in the 24-year-old case. Robert was 16 years old when Chicago Detective James O'Brien, a known associate of Jon Burge, took him from his grandmother's home and later arrested him for murder. Johnson turned 41 this year at Hill Correctional Center -- finally, with some hopeful news to celebrate. An Illinois appellate court has reversed the dismissal of his post-conviction petition and sent his case back to the circuit court for an evidentiary hearing, at which his lawyer from the Exoneration Project can present the new evidence supporting his innocence.

Our investigative podcast series, Somebody, has received renewed attention this summer: the New York Times put it at the top of its list of "True Crime Podcasts at the Intersection of Race," Buzzfeed mentioned it in a piece on the future of the true crime genre in the George Floyd era, and Harpers Bazaar featured it among "22 Podcasts You Should Be Listening to in 2020.”

As part of the campaign to raise public awareness about the Green case, organizers across the city collaborated on a rapid response campaign called Release the Records. Using a traveling, interactive art installation, “Library of Misconduct,” Invisible Institute team members encouraged attendees at rallies to read and explore complaint narratives. Contact maira@invisibleinstitute.com to request the art installation at your event.

The SHOWTIME documentary 16 Shots, co-produced by the Invisible Institute, has received Emmy nominations in three categories: Best Documentary, Outstanding Investigative Documentary, and Outstanding Research. Winners will be announced on September 21.