Vol. 3 Issue 8

A Note from Jamie Kalven on Studs Terkel

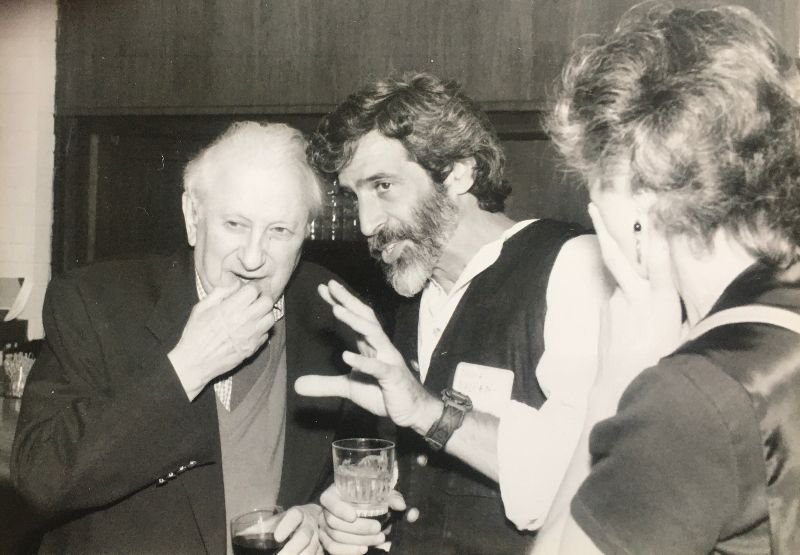

Studs Terkel and Jamie Kalven in conversation, 1994

On May 13, 2021, Jamie Kalven accepted the Ripple Effect Award from Public Narrative:

This award is an unexpected gift. In several respects.

First, as we emerge into spring after our plague year, it’s a joy to join in Public Narrative’s annual celebration. No event makes the Chicago journalism community visible to itself the way this one does.

And it is an honor to receive the Ripple Effect Award. The meaning of this award for me is deepened by the fact that the first recipient was Nikole Hannah-Jones. Nikole was a superb journalist before she conceived and executed the 1619 Project, but she became a transcendent force with that extraordinary contribution to our understanding of who we are and of what journalism can do.

Above all, I am grateful to have occasion to summon forth the patron saint of Public Narrative and my old friend: Studs Terkel. Studs has been a presence throughout my life. There is a sense in which I grew up inside his voice. The radio station that was his original and longtime home—WFMT—was always on in my parents’ house. It was the medium through which my siblings and I moved growing up. And Studs was on the air a lot in those days—at 10:00 a.m. on weekday mornings, and then again on Sunday evening. For me as a child, the sound of his voice conjured the richness of the wide world beyond the household and carried the promise of how much of that richness a single sensibility could absorb without bursting. Together with my father, Studs embodied for me the joys and possibilities of conversation. They planted the seeds of the conviction, central to my understanding of both the First Amendment and my practice as a journalist, that there is nothing that cannot be talked about.

I was also infected, at an impressionable age, by Studs’ sense of style—expressed in the way he signed off at the end of his show with a Depression era phrase popularized by Woody Guthrie. “Take it easy,” he would say, “but take it.” As a kid, I loved that note of nonchalant defiance. I still do.

When I was perhaps twelve years old, I heard words issuing from the radio that I registered with startled recognition as if they were already written in my soul. The program was “Born To Live,” a collage of voices created by Studs and his colleague Jim Unrath. The words were spoken by William Sloane Coffin, then the chaplain at Yale University. The occasion was the invocation at a graduation ceremony sometime in the 1960s. It became a WFMT tradition to rebroadcast “Born To Live” on New Year’s Day. Each year the Kalven family would gather in the living room to listen. As Studs’ inspired orchestration of voices and music unfolded—Bertrand Russell yielding to James Baldwin then to a Hiroshima survivor then to a sharecropper in the Mississippi Delta—I would wait for Coffin’s invocation. It became for me something akin to a New Year’s resolution.

Over the years, I noticed that Studs frequently quoted Coffin’s words on public occasions. Of all the words he had taken in and deeply heard, these words seemed to resonate for him with special power and clarity. Toward the end of his life, over drinks at his place, I asked if he could give me a cite to the Coffin benediction. He went upstairs. I could hear him rummaging around and mumbling. A few minutes later, he came down and handed me a sheet of paper on which he had written out in pencil what I have come to think of as “Studs’ prayer.” Framed, it now hangs on the wall of my office. [See original at bottom of the newsletter.] Here it is:

Oh Lord, as we leave this university, let these be young men and young women for whom the complexity of issues only served their zeal to deal with them; young men and young women who alleviated pain by sharing it; and young men and young women who were always willing to risk something big for something good. So that we may have in the world a little more truth, a little more justice, a little more beauty than would have been there, had we not loved the world enough to quarrel with it for what it is not but still can be. Oh God, take our minds and think through them, take our lips and speak through them, and take our hearts and set them on fire.

I can think of no better way of describing the sort of journalism that Studs modeled and that I, like so many in this virtual room, aspire to practice than a lover’s quarrel with the world “for what it is not but still can be.” Passionate attachments—to places, to people, to causes, to life itself— do not preclude rigorous inquiry and reporting of the highest quality. Indeed, they can enable it. Detachment has its place, but there are things that can only be learned about the world and can only be reported accurately, if you care.

Such an orientation opened Studs— and those of us who follow his example— to charges of being advocates as opposed to that mythical being the objective journalist. Ultimately, the only rebuttal to such criticism is the work itself. But there is an irony here worth noting. To dismiss Studs as doctrinaire misses precisely what was so exemplary about his way of being in the world: his immense appetite for being surprised by life. He elicited the voices of others not in the expectation they would illustrate some thesis but in the hope they would delight him by refusing to conform to his preconceptions and so carry him deeper into the world.

Influence— this business of ripple effects— is a mysterious matter. There is always a danger, if you believe your press clippings, that you will be deluded about the extent of your impact. That said, it has been my great good fortune to be joined in recent years by an extraordinary group of younger colleagues who have embraced the values that animate my work and have made them their own. The result has been the creation of the Invisible Institute, an adventure that continues to unfold. So I dedicate this award for my past work to the Invisible Institute team and the work that lies ahead.

Jamie Kalven reported in The Intercept on the

role the ShotSpotter technology played in the police killing of 13 year-old Adam Toledo. And Kalven and Madison Muller, a reporter at the South Side Weekly, broke the story of what video footage of the police killing of 22 year-old Anthony Alvarez would reveal when it was released by the City. Kalven appeared on Chicago Tonight to discuss the Alvarez incident.

The Somebody podcast has recently been awarded with first place in the National Headliner Award for Criminal Justice Podcast, the Scripps Howard Award for Excellence in Radio/Podcast Coverage, five Peter Lisagor Awards —for Best Investigative Reporting in All Media Categories, Best Feature Series in All Media Categories, and Best Podcast, New Podcast, and Podcast Episode — and a nomination for the Ellie Award, by The American Society of Magazine Editors.

Our co-reporting on Mauled received a Katharine Graham Award for Courage and Accountability, given by the White House Correspondents Association, and first place in the National Headliner Award for online investigative reporting for digital partnerships.

"Studs' Prayer," transcribed in the opening essay