Vol. 3 Issue 14

Seeking new ways of knowing within our human rights reporting practice

A note from Alison Flowers:

May 18, 2022

When I joined the Invisible Institute seven years ago, I could count our team members on one hand. Our flagship database, the Citizens Police Data Project, did not yet exist. We were not yet known for breaking the story of the police murder of Laquan McDonald. The Watts scandal had not yet emerged into view. The Somebody podcast – or any podcast – was not even a thought in our minds. And the substance of what would become the Chicago Police Torture Archive, the first human rights documentation of the Burge torture era and its ongoing harms, was buried in file cabinets, trauma, and memory.

Today, many investigations and productions later, we are gratified by the recognition our work has received. The Invisible Institute is hardly invisible anymore. Yet looking ahead we recognize how resistant to change the structures of racial inequality are.

This is nowhere more apparent than in the work of our wrongful conviction unit. The team is small. The work is painful. And painfully slow. Against a tide of inquiries, we usually can only take one case at a time. Visits to Illinois prisons feel like trips back in time, as we make our way to media conference rooms amidst a sea of incarcerated Black men, including elderly inmates leaning on walkers.

Proving innocence is always a longshot, regardless of the truth. Decades after a conviction, evidence may have been destroyed, witnesses may have died and appeals have been exhausted. So what can we possibly do?

Central to our work is the effort to illuminate through investigation and data analysis the role of police abuse in mass incarceration and the maintenance of racial inequality. Across the country, official misconduct is a contributing factor to more than half of exonerations (56 percent of cases, as of this writing), second only to false accusations (61 percent of cases), with which it is entangled. About 39 percent of all exonerations nationwide specifically involve police misconduct. In Cook County, the number is much higher: More than three-quarters of exonerations involve officer misconduct. Of those cases, the wrongly convicted were overwhelmingly Black – more than 86 percent.

There has been some progress and promise in recent years. The mass exonerations of former police officer Ronald Watts’ victims continue to climb in number. Since Jamie Kalven first reported on Watts’s criminal enterprise in the Code of Silence series, 171 individuals have been exonerated and 212 convictions have been overturned (some exonerees had more than one conviction).

In 2020, we published a yearlong investigation into the case of Robert Johnson, which in part examined the actions of Detective James O’Brien, an associate of the torturer-commander Jon Burge and uncovered new evidence. Johnson has now been granted an evidentiary hearing.

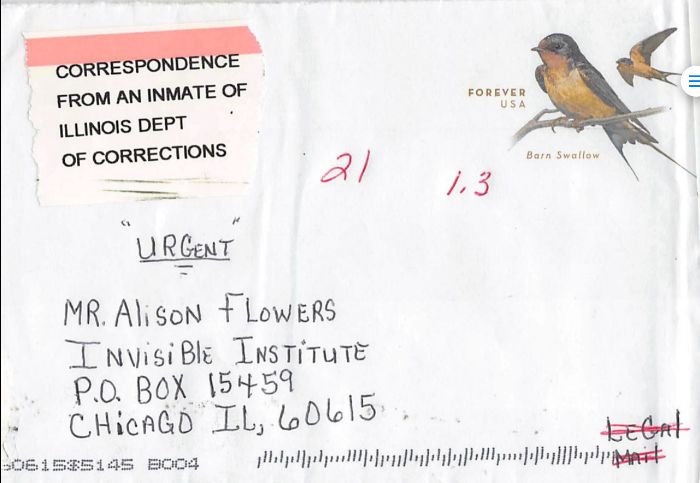

As we prioritize cases at the nexus of police misconduct, race and wrongful conviction, the Invisible Institute seeks to discern patterns. Working with Civis Analytics, we created a database of hundreds of handwritten letters from potentially wrongly-convicted prisoners and cross-referenced them with Cook County exoneration records. The project produced an algorithm using natural language processing that can help identify police and prosecutors, with the hope of unearthing trends buried within cries for help from the incarcerated.

Central to human rights work is the principle that we as citizens have a moral obligation to know what can be known about violations of human dignity and to act on that knowledge. Our practice at the Invisible Institute is directed toward fashioning new ways of knowing that extend the reach of that principle. A recent case in point: A new study using five decades of data on police misconduct collected by the Invisible Institute found evidence of at least 160 possible misconduct-committing officer crews consisting of 1,156 police officers. These officers comprise less than four percent of the police force, yet they account for approximately 25 percent of all use of force complaints, city payouts for civil and criminal litigations, and police-involved shootings.

There is a power in that knowledge. Together, we will continue to expose these truths, whether they are buried in complex police data or handwritten on notebook paper from a prison commissary.

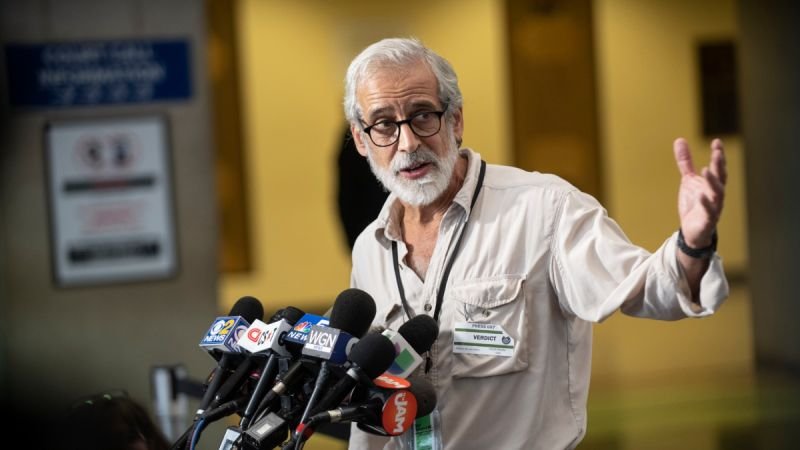

The Nieman Foundation at Harvard awarded Jamie Kalven the 2022 I.F. Stone Medal for Journalistic Independence, recognizing “his body of work that includes investigations and ventures that have documented police abuse and impunity, provided access to vital public records and have told the stories of many of the underserved and underrepresented residents in long-neglected public housing projects.”

61st Street, an 8-episode dramatic series on which Jamie Kalven worked as consultant, premiered on April 10 on AMC, AMC+ and ALLBLK. Block Club Chicago reported on the series, and it was reviewed in the Chicago Tribune and Chicago Sun Times.

Development director Anwulika Anigbo exhibited work alongside Jazmine Harris, Maria Gaspar, and SHENEQUA at EXPO CHICAGO this year. For Freedoms presented "Another Justice," an exhibition of four Chicago-based artists who exemplify the values of abolition.

Development director Anwulika Anigbo exhibited work alongside Jazmine Harris, Maria Gaspar, and SHENEQUA at EXPO CHICAGO this year. For Freedoms presented "Another Justice," an exhibition of four Chicago-based artists who exemplify the values of abolition.

These are examples of the work your support helps make possible.